“Here’s the smell of the blood still: all the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand.”

“Here’s the smell of the blood still: all the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand.”

(Macbeth, act 1, sc. 5)

Part 1

During this summer of our discontent, much has been said and written about the massacre of the Palestinians in Gaza, the civil war in Ukraine and the downing of the Malaysian Airliner. To those whose “eyes are not like their judgments, blind!” (1) or whose “eyes are not made the fools o’ the other senses” (2) the thread linking these abominable events is “as clear as is the summer’s sun.” (3) Unless of course, the reader believes the tales propounded by the regime-media parrots who “… construe things after their fashion, clean from the purpose of the things themselves.”(4).

On Israel’s Nazi-style extermination of the Palestinian, we may still note that “the offence is rank, it smells to heaven; It hath the primal eldest curse upon’t, A brother’s murder” (5). But to repeat or re-hash what is already known would amount to duplicating Polonius when he says that “to expostulate …why day is day, night is night and time is time, were nothing but to waste night, day and time.” (6)

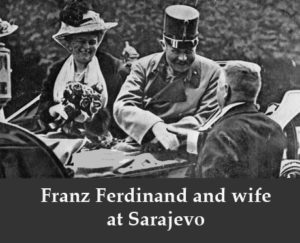

However, as we know, this summer 2014 is also the 100th anniversary of the summer of 1914, when a “murder most foul, as in the best it is” (7) was committed in Sarajevo, followed a few weeks later by the beginning of WW1 and the consequent slaughter of millions.

Given that history is said to be instructive, it may interest some readers to know (or recall to memory), something more about the characters involved in the Sarajevo event, prior to that European apocalyptic catastrophe.

As mentioned in a previous blog (Shakespeare, French Revolution and World War 1) the 19th century witnessed the transformation of major European ethnic groups into national states that gnawed lands away from old empires. The most affected were the Ottoman and the Austro-Hungarian empires. Concurrent with nationalism, there existed a long-standing conflict, that we could call cultural, between the European Catholic West and the Orthodox Slavs of the East, notably the Russian Empire and the South Slavs of Serbia. As Tolstoy noted in the post-script of “War and Peace”, the disastrous Russian campaign of Napoleon in 1812 was one manifestation of the conflict. More in general, the Slavs, notwithstanding their remarkable achievements in the world of letters and of the mind, felt treated as ‘inferior’ by the West. In this context we may remember that “Slav” is a term of late-Roman Empire origin, meaning ‘slave’. A coarse comparison would be the general attitude towards Latinos in America.

In XIX century Russia, in an attempt to show Russia’s willingness to become part of the “European Concert” it had become common to adopt French as a second language. Readers of “War and Peace” and of other XIX century Russian novels will remember that often the characters express themselves in French.

In the Balcans, Serbia had gained her independence at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, and so did Bulgaria, Romania, Macedonia and Montenegro. There remained lands that still belonged to the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, notably Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Croats were mostly Catholic, whereas in Bosnia there was a mixture of Croats (Catholics), a majority of Serbs (Orthodox) and a mixture of Croats and Serbs who had converted to Islam during the centuries of Ottoman rule.

Though close in language and somatic traits, the Croats had never felt a close kinship with the Serbs. During the trial of the Sarajevo assassins, a Croat was asked if he liked the Serbs. “I do – he replied – when I don’t see them.”

After the turmoil following the wars of independence against the Turkish Empire, Austria had taken administrative control of Bosnia-Herzegovina, followed by a formal annexation in 1908. We can consider this annexation as the proximate cause of friction between Serbia and the Austrian empire, leading eventually to the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914.

Let’s now briefly look at the main characters on the Austrian side of the conflict. The aging Emperor Francis Joseph’s son, Crown Prince Rudolph, is probably the best-known member of the Emperor’s family, thanks to the Hollywood movie of the  Mayerling Incident of January 1889. In the incident, still surrounded by mystery, the 30-year old crown prince and his 17 year old lover Baroness Mary Vetsera were found dead in the Mayerling hunting lodge near Vienna, apparently victims of a murder-suicide. This explains why the heir to the Austrian throne was the eventually murdered Franz Ferdinand, nephew and not son of Francis Joseph.

Mayerling Incident of January 1889. In the incident, still surrounded by mystery, the 30-year old crown prince and his 17 year old lover Baroness Mary Vetsera were found dead in the Mayerling hunting lodge near Vienna, apparently victims of a murder-suicide. This explains why the heir to the Austrian throne was the eventually murdered Franz Ferdinand, nephew and not son of Francis Joseph.

The emperor wife’s Elizabeth, was also assassinated in 1898 in Geneva by an Italian anarchist.

Elizabeth’s nephew was the eccentric Ludwig II of Bavaria, who, when declared insane and  attempting to escape from his pursuer, strangled him. Together they both drowned in a nearby lake. Ludwig II of Bavaria is also indirectly famous in America for having built Neuschwanstein, the castle of Walt Disney’s “Sleeping Beauty”.

attempting to escape from his pursuer, strangled him. Together they both drowned in a nearby lake. Ludwig II of Bavaria is also indirectly famous in America for having built Neuschwanstein, the castle of Walt Disney’s “Sleeping Beauty”.

The emperor’s brother Maximilian, was nominated by the Mexicans to be their emperor, when they couldn’t agree on who should run the country. Maximilian’s decision to accept the nomination proved fateful, as the Mexicans shot him against a wall.

And now to Franz Ferdinand, killed at Sarajevo.

One of most fateful influences on his life was his marriage. It was at first rumored that he had focused his attention on the Archduchess Marie Christine, a lady of great eminence for the glory of her lineage, the influence of her acquaintances and the splendor of her assemblies. She was gifted with every excellence that can impress awe upon the mind of man.

All in all, Marie Christine came from a family of adequate standing to produce a future empress. Besides, fortune influences affection and the marriage was believed imminent. Franz Ferdinand frequently visited their castle at Pressburg, but it was only pretense. He had fallen in love with one of the ladies-in-waiting in the household, Countess Sophie Chotek.

One small incident gave away the secret. Shakespeare would say,

“And in such indexes, although small pricks

To their subsequent volumes, there is seen

The baby figure of the giant mass

Of things to come at large.” (8)

After a tennis party at Pressburg, Franz Ferdinand changed his clothes but forgot his watch. A servant brought it to the Archduchess Isabella, mother of Marie Christine. She opened the locket expecting perhaps to find a photograph of her daughter. Instead she found the photo of one of her ladies-in-waiting, Countess Sophie. Miffed, or rather enraged, the mother dismissed Sophie on the spot and commanded her to leave the house that very night.

What followed is a plot endlessly repeated throughout history and literature. Franz Ferdinand loved Sophie “with so much of his heart that none was left to protest.” (9) The Hapsburg relatives did their best to prevent the marriage – the prospective bride, being only a countess, was debarred from being eligible (ebenbürtige).

The strenuous opposition of the Emperor was matched by the stern determination of his nephew, who was prepared to give up the right to the throne. There were no other options – therefore the Emperor gave his consent on one condition. The marriage had to be ‘morganatic’ – meaning that neither the bride nor any children of the marriage could have succession rights, titles, precedence, or could inherit property.

Those who, like this writer, are “snappers up of unconsidered trifles” (10) may like to know that “morganatic” comes from the Medieval Latin ‘matrimonium ad morganaticum’, where ‘morganaticus’ was a traditional gift made by the bridegroom to the bride the day after the wedding. But that ‘morgan’ in ‘morganaticus’ sounds more Anglo-Saxon than Latin. The dilemma was solved by a 16th century Jesuit who compiled a dictionary of secondary Latin. Where he explained that ‘morganatic’ is a marriage by which the wife and the children who may be born are not entitled to any share in the husband’s possessions other than the ‘morning-gift’.

There were some practical consequences following the morganaticness of the marriage. At functions, for example, Sophie would have to sit at the end of the table or after the last lady of suitably noble rank. And her son could not and did not become the last Emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Sophie felt slighted at Court. On the other hand, the German Emperor Kaiser William liked the couple. During an official visit to Berlin, Kaiser William arranged the seating at the reception using a number of round tables. And Sophie did not have to endure at the table the humiliation of the enforced distance from her husband, due to her inferior rank.

But perhaps, the most fatal consequence was the lack of adequate security when Franz Ferdinand and his wife visited Sarajevo and both were assassinated. His last words were, “Sophie, Sophie, do not die. Live for our children.”

In a following blog we will explore the characters on the Serbian side of the plot.

Context of the theme quote in the play. Lady Macbeth, now insane, sleepwalks and utters sentences related to the bloody deeds she was involved in.

Note. The quotations in Italics in the text are (in sequence) from (1)Cymbeline, 4.1 – (2) Macbeth, 2.1 – (3) — Henry V, 1.2 — (4) Julius Caesar 1.3 – (5) Hamlet 3.3– (4) Julius Caesar, 1.2 – (6) Hamlet 2,2 – (7) Hamlet, 1.5 – (8) Troilus and Cressida, 1.3 – (9) Much Ado About Nothing 4.1 – (9) Winter’s Tale 4.3

Image Location. http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Guardian/Pix/pictures/2013/6/20/1371746375009/Franz-Ferdinand-008.jpg