🏛 Return to Your Daily Shakespeare

📄 Mnemonic Frame Technical Instructions

Shakespeare in Pictures

Mnemonic Frame Database

Below are links to various installments of the Shakespeare In Pictures interactive Mnemonic Frames. Click the links to open an installment in a new tab. Use the VIEW menu and select SLIDESHOW to begin each presentation.

More installments and Mnemonic Frame collections will be added on an on-going basis.

Before diving in, you might care to read through some Some practical hints, considerations and an example on usage.

Here is the entire collection of the first 100 Mnemonic Frames, with the graphics first, followed by the quote.

If you wish to go through the collection in installments, you will find them below.

Installment #1 includes 15 quotes and 30 Mnemonic Frames, including memorable quotations from Antony and Cleopatra through Coriolanus. The beginning of your journey into mastery through memorization.

Installment #1, image first: Click or tap here to open in a new tab.

Installment #1, quotation first: Click or tap here to open in a new tab.

Installment #2 is a further 15 quotes and 30 Mnemonic Frames. This installment wraps up Coriolanus and continues through Hamlet.

Installment #2, image first: Click or tap here to open in a new tab.

Installment #2, quotation first: Click or tap here to open in a new tab.

Installment #3 is live! This installment begins with additional quotations drawn from Hamlet and continues through King Henry VI, Part 2.

Installment #3, image first: Click or tap to open in a new tab.

Installment #3, quotation first: Click or tap to open in a new tab.

Some Practical Hints, Considerations and an Example on usage

Note: Edward Gibbon (1737- 1794) was an English rationalist, historian and scholar. He is best known as the author of “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”, a massive continuous narrative, from the 2nd century AD to the fall of Constantinople (1454).

In his autobiography Gibbon describes his own method to acquire the knowledge and mastery of the Latin language. Here we are not dealing with Latin, but the Mnemonic Frames system applies essentially Gibbon’s idea(s), transformed into a much simpler and (we may agree), more self-rewarding implementation – considering that we live 250 years after Gibbon. Here is what he said,

“In my French and Latin translations I adopted an excellent method, which, from my own success, I would recommend to the imitation of students. I chose some classic (Latin) writer, such as Cicero and Vertot, the most approved for purity and elegance of style. I translated, for instance, an Epistle of Cicero in French; and, after throwing it – the Latin original – aside, till the words and phrases were obliterated from my memory, I re-translated my French into such Latin as I could find; and then compared each sentence of my imperfect version with the ease the grace, the propriety of the Roman orator.” Here is how we can apply Gibbon’s principle or method, simplified, lightened and almost made recreational, to the Mnemonic Frames.

- Select a quote to memorize – read it and/or repeat it aloud.

- Look at its related Mnemonic Frame. The quotes online, in the book-related collection, are divided into two files. In one the words-of-quote come first and the related Mnemonic Frames follow. In the other the Mnemonic Frames come first and the associated quotes come later. The idea being that, at the beginning, you use the written-quote-first file. Then when the quotes begin to imprint themselves in your mind, you use the Mnemonic-Frames-first file and linger on the written quote if and only when you need to cast a quick look at the printed original.

- Make an immediate attempt to repeat the quote, looking exclusively at the associated Mnemonic Frame.

- Depending on the length and complexity of the quote, there will be various switchings between a quote and its associated Mnemonic Frame.

- You can start with either of the two files, that is the word version or its Mnemonic Frame rendition. However, it is recommended to start with the ‘quote first’ file as you are memorizing the quotes. The ‘Mnemonic Frames first’ method is better suited when you have already mastered the quotes and will only need to check the actual original Shakespeare’s words to verify the accuracy of your recollection.

More in general, we may think of our memory as a musical instrument that can be played to its full potential, when properly trained. After mastering a challenging musical passage (referring here to timing, fingering and variations in volume and pace, etc.), subsequent others that require the same or similar set of skills will become easier and almost effortless to play. Eventually you may not even associate the ease in executing a new difficult passage with the ease achieved in executing the original challenging passage.

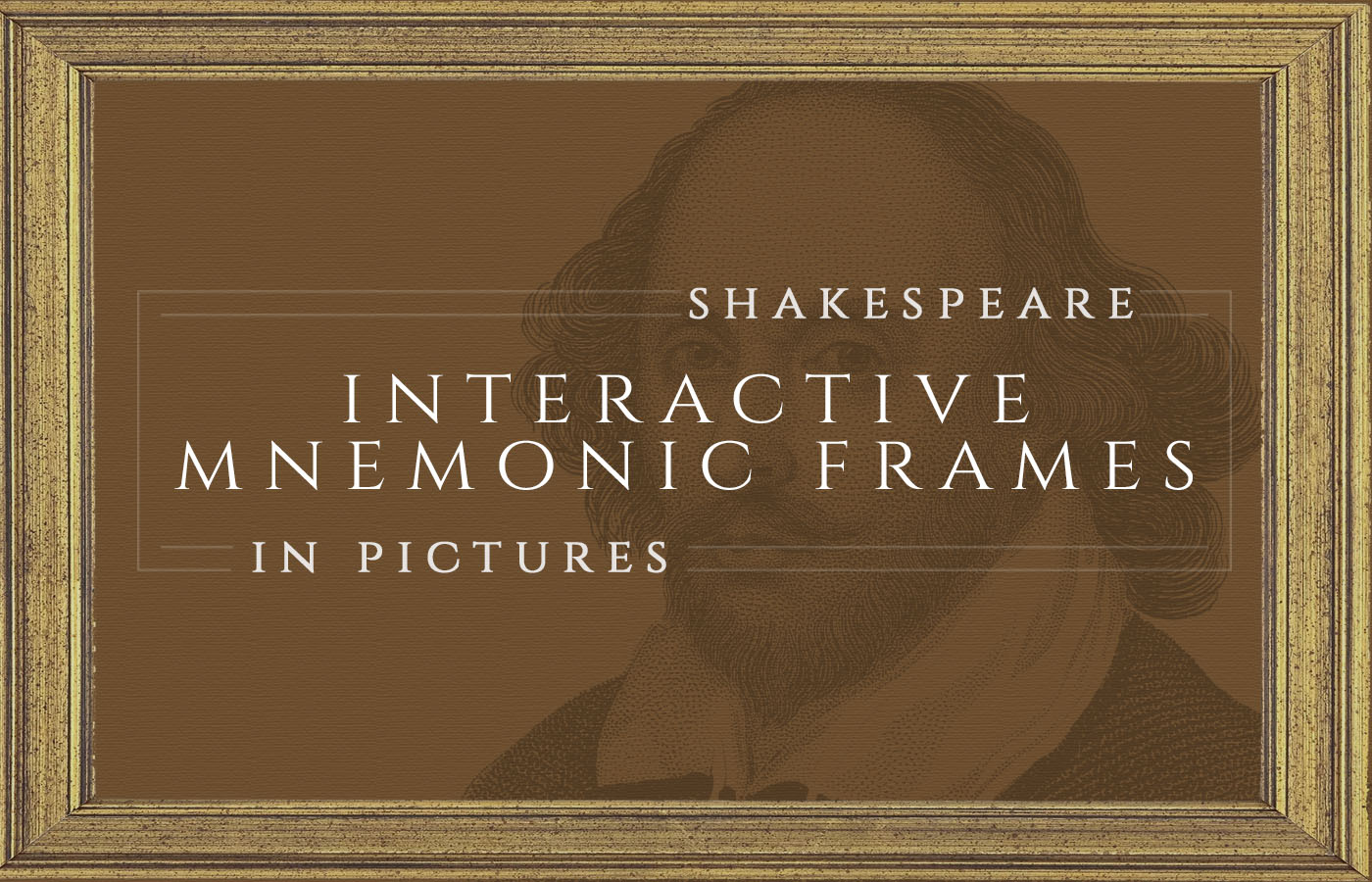

Example 1:

“(He is) … the lyingest knave in Christendom” (KHVI p2 2.1)

Mnemonic Frame:

This is a simple quote. You will likely find that the images of the Mnemonic Frame will quickly require no reference to the actual printed words of the quote for prompt recollection. Both the images of Pinocchio and of the knave are sufficiently powerful as to drag in their train the map of ‘Christendom’. The accents do the rest – the lyingest knave in Christendom.

In a short time you will probably not even need to look at (or think of) the Mnemonic Frame, it may be one of the quotes that are automatically and permanently stored in your ‘Shakespearean mental safe.

That inexisting superlative (lyingest), takes the sting out of the insult. That obsolete characterization (knave), transforms the target of the barb into an amusing vignette. And that wide, yet at the same time restrictive area of application, ‘Christendom’, rather than the more comprehensive term ‘world’ adds to the scene a touch of indirect familiarity.

Conclusion: the barb has not lost its sting and puts its utterer into a win-win situation. If the target feels or appears offended, he shows the lack of a sense of humor. If he laughs he acknowledges the power of wit, without necessarily admitting, to the utterer of the barb, that he is right. More in general, these are the characteristics of a win-win situation.

And given that politics is a notorious realm of lying, the quote may bring to mind in its train, for example, another quote connected with electoral promises, from ‘Timon of Athens’, “Promising is the very air o’ the time: it opens the eyes of expectation: performance is ever the duller for his act… “

I mentioned this particular connection not because it may be exactly duplicated in your mind, but to show how our minds elaborate information and, automatically or instinctively, are driven to their individual ‘arsenal’ of personal quotes, once the occasion calls for it and the recalled expression is associated with a Mnemonic Frame.

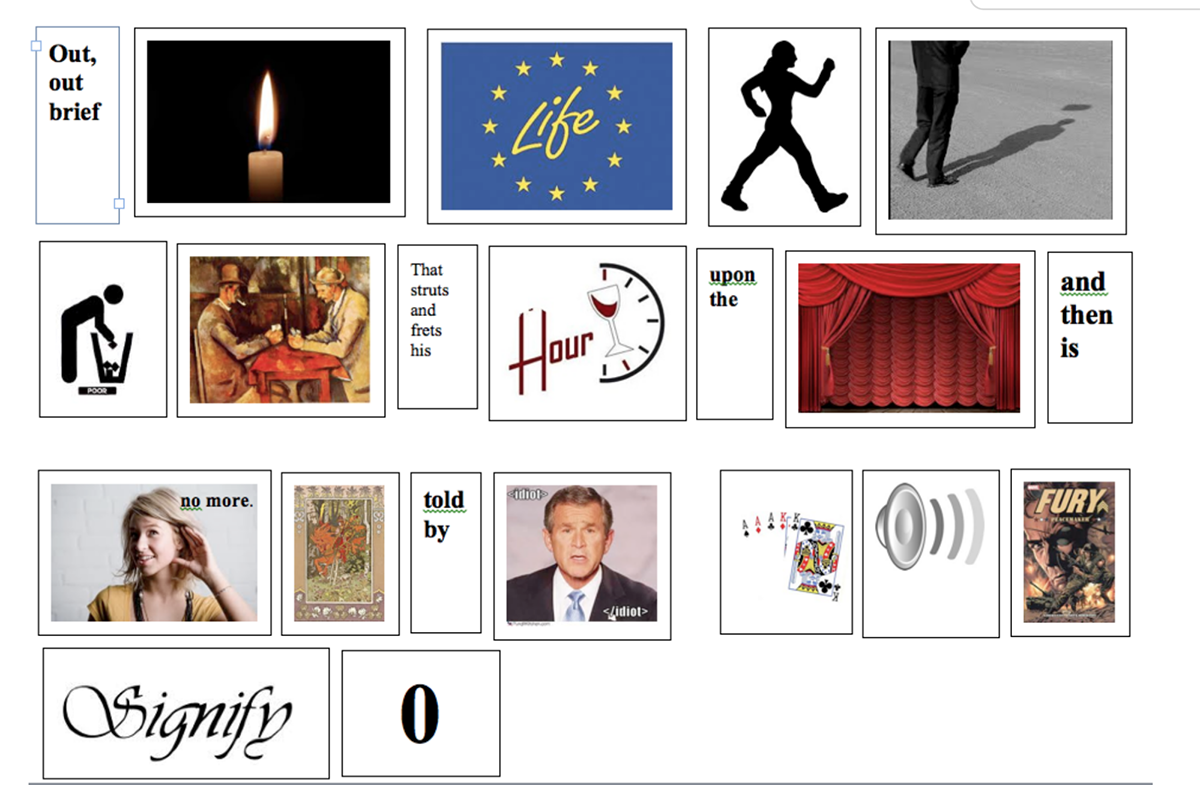

Example 2:

“To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death…”

Mnemonic Frame:

Note:

For this quote the associated Mnemonic Frame has been split into two sections. And given the nature and the length of the quote, more use has been made of words-turned-into-pictures elements. Why? There are several reasons, listed not in order of importance.

a) Splitting the quote into two sections simplifies the task of recollection for the mind.

b) There are some ‘anchor’ elements of the quote (both in terms of words and images) that the mind can instinctively use as ‘memory anchors’ on which to append the rest, particularly in the last row, ‘lighted’, ‘fools’. ‘Dusty’, and ‘death=skeleton’.

c) In the first two lines more use has been made of ‘pictorialized’ words. Experience has shown that a Mnemonic Frame must achieve a compromise between images that refer to words without any ‘intermediary’ and words that are themselves semi-transformed into images. As the quote becomes imprinted into the memory, each practitioner will handle these words-turned-into-images, (partially or completely) differently. And this according to what we can define as his/her ‘imprinting’ pattern or preference (mostly instinctive). There is no ‘perfect’ pattern – one component of the effectiveness of the system consists in the freedom that each practitioner has to shape the system to suit his pattern of association which is similar, but rarely exactly the same between memorizers. A subject of potential immense scope, as it involves the full spectrum of psychology, history and relevance of personal memories etc. For, whether we may decide to ignore it or not, each thought of ours concentrates the experience and the effects of the thousands and millions of thoughts that have visited our mind at one time or another.

In the instance, the first four frames, rely chiefly on their combined rhythm to imprint the line into memory. ‘Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow’ requires no effort, because if you decided to memorize the quote, you would implicitly identify and ‘index’ the quote in the mind with these words. ‘Creeps in, this petty pace from day to day’ suggests a rhythmic forward movement, as indicated by the bolded and larger letters.

Thinking of time as measured in syllables is a sufficiently original image, the pictorialized word ‘syllable,’ followed by the pocket watch with inscribed script should imprint the sequence of the frames, including those ‘yesterdays’ that act as a prelude to the last line of the Mnemonic Frame. In which (the last line) the mind may find some soft satisfaction in reading without any difficulty the words in the images. The unspoken reasoning may be approximately as follows, “Of course, “theater powerful lamp” -> have lighted, “fool symbol” as symbol of all fools, “one way only sign” -> how ineluctably true this is along with what follows, the image(s) of “dusty death.”

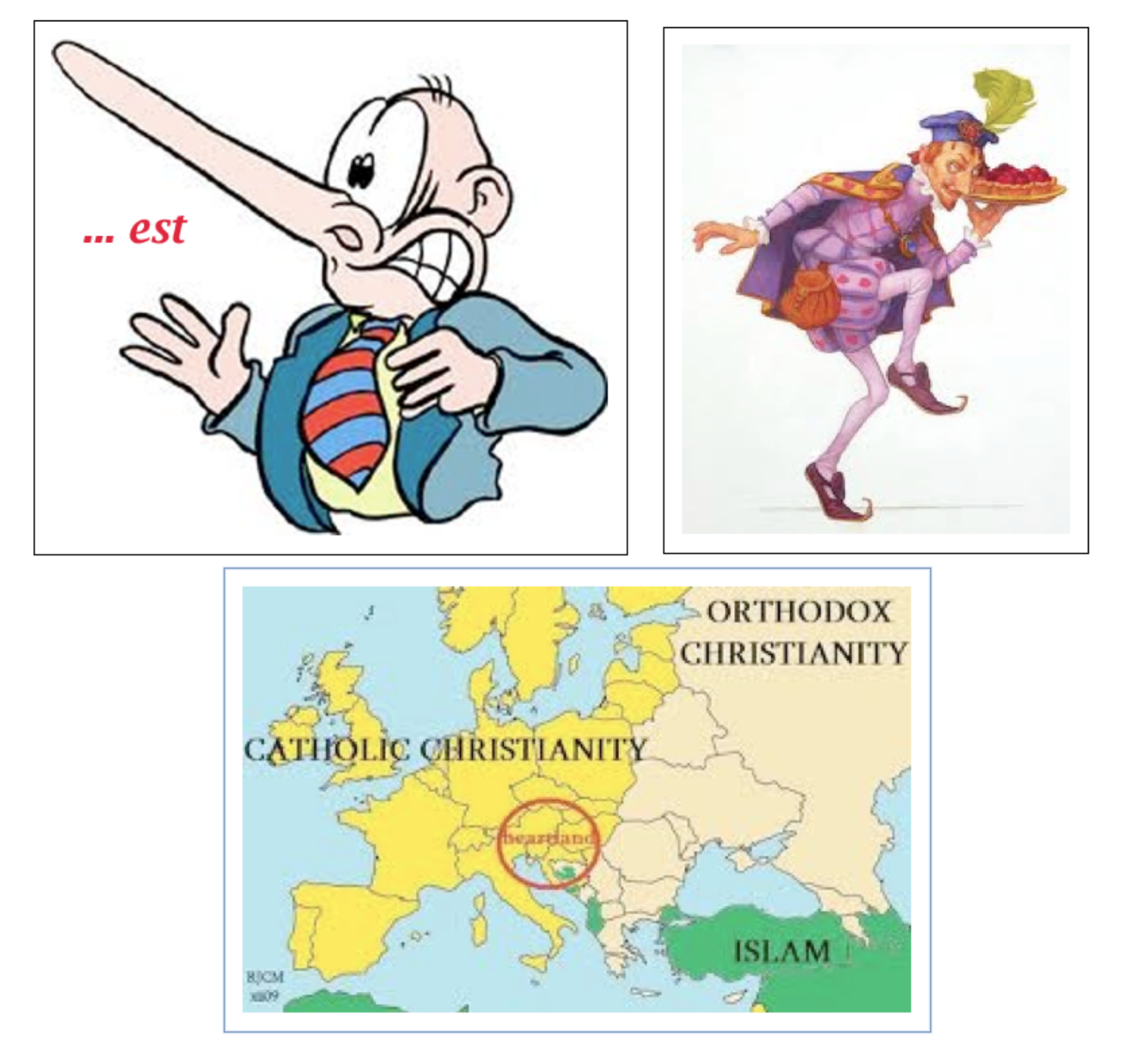

Example 3:

… Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

Mnemonic Frame:

In the second part of the quote, the analysis of the logical correspondence between the original words of the quote and its individual Mnemonic Frame(s) is self-evident. However, for consistency, here is a summary.

In “out, out brief candle, life’s but a walking shadow”, note how the accent pushes forward the action.

That wave of accents that push the action forward continues until the Mnemonic Frame of the ‘stage’. ‘… as well as with “and then is heard no more,” that concludes concisely the ‘strange, eventful history’ (As You Like It).

In the concluding and equally sombering, pessimistic and yet philosophical considerations bring the scene (and the Mnemonic Frame) to a close. The rhythm relents, widens, suggesting the image of the estuary of a long river, where the water loses its individuality as part of a river and becomes part of a completely indistinct and different whole.

In Summary

The choice of the quote (“Tomorrow and tomorrow…”) for this analysis is arbitrary, including its indirect suggestions and associations. But, as discussed more at length in the printed version of the book ‘Shakespeare-in-Pictures’ and in more specialized literature, each person, instinctively and often without actual realization, finds, in certain lines, the type of associations outlined in the previous example.

Which is but one reason why Shakespeare’s words make the same (and perhaps even greater) impact 400 years after he left us, while others, maybe perceived at the time as ‘full of sound and fury’, have been mostly forgotten, along with their utterers. That is, they sounded ‘full of sound and fury’, but in the end they ‘signified nothing’.

On the Practical Applications of the Quotes

So as to keep the volume of this endeavor within limits, the number of quotes and associated Mnemonic Frames have been limited to 100. However, this does not mean that all the quotes have to be applied in their entirety to be effective. For example,

“To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time…”

…can be applied as an ironic-sarcastic comment to any situation in which a delay in taking action appears to be motivated by a plan to avoid taking a decision, more or rather than a practical difficulty to proceed with the plan.

“… Life’s but a walking shadow… signifying nothing” can dramatically express a profoundly skeptical, yet at times realistic opinion or attitude towards events in which you may or may not be directly or even indirectly involved. Yet… we equally find in Shakespeare the means to lift our spirit above ‘the swamp’ and its deleterious effects. As in, for example, also in Macbeth,

…Though all things foul would wear the brows of grace,

Yet grace must still look so

The point being that, once you have made a certain # of quotes part of your ‘resident’ verbal armor, you will find their applications suggesting themselves to you essentially without effort. The situation being similar to having a well structured inventory of physical items, which expedites and facilitates their individual retrieval and use.

The “Shakespeare-in-Pictures” mixed book-plus-online-combination is actually the natural extension of the comprehensive situational dictionary, “Your Daily Shakespeare – an Arsenal of Verbal Weapons to Drive your Friends into Action and your Enemies into Despair” – the ONLY Shakespearean work of this type. In the dictionary, all entries have the following structure:

- The situation

- The applicable quote

- Suggestion(s) on how to apply it in various circumstances

- Description of the context in which the quote appears in the play, poem or sonnet

An analytical index with more than 10,000 entries, directs the user to match a situation with one or more suitable Shakespearan quotes. In essence “Your Daily Shakespeare” is the most effective guide, tool and manual for anyone whose aim is to prepare and/or deliver a message that is simultaneously effective, elegant and memorable.

For what is worth, he who writes here, started a computer company from the proverbial nothing. He did not “ride the tide of pomp that beats upon the high shores of the world” (Henry V, 4.1), and all he had to rely upon was the hope that some influential computer magazine picked up his articles, which is what happened. The following very short TV interview on a major channel in Portland Oregon shows, better than any words, a concentrated record of the event, as well as, the dramatic effect and damage that forty winters plus deliver to anybody’s brow.

Yet, this event would probably have not occurred had it not been “prepared” by the publicity obtained from articles (written with a classical or Shakespearean flavor) in various magazines.

Ending Thoughts for a Beginning

With the ‘Mnemonic Frames’ I dedicated myself to the investigation of a question of which, without visible inconvenience, the world may expire in ignorance (Dr. Johnson). As with many human endeavors, the theory about Mnemonic Frames should be rated as sufficiently probable to afford a basis for experimentation without prejudice.

In the improvement of language skills (inevitably linked with a familiarity and command of Shakespearean quotes), we may think of language as a musical instrument. Where any progress yields satisfaction both to the player and to the audience.

To ensure continuous progress, acquisition, familiarity and repetition of quotes (via Mnemonic Frames) should become a habit.

One most instructive reference and critical distinction between a habit and a maxim (that is a proverb, a slogan, a precept or similar), Swiss educator Frederic Amiel made, in my view, the important and critical observation.

“In the conduct of life habits count more than maxims, because habit is a living maxim, it becomes flesh and instinct. To reform one’s maxims is nothing: it is about to change the title of a book. To learn new habits is everything, for it is to reach the substance of Life. Life is but a tissue of habits.”

Personally I found it both illuminating and motivational, especially in those moments where it would be tempting to let go of the habit in exchange for a more immediately amenable use of time. …And I even made a Mnemonic Frame for it, so as to be able to promptly recall it, in all its strength, when needed.

If you wish to receive that Mnemonic Frame, representing the observation bt Fredric Amiel, just send me an email and I will forward it to you.